FIRST ASIANS

Archaeologists

Find Central Asia Civilization As Old As Sumeria

May 5, 2001 - Linda Moulton Howe

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

A large sophisticated

civilization equal to Sumeria and Mesopotamia and thriving at the same time at

least 5,000 years ago was lost in the harsh desert sands of the Soviet Union

near the Iran and Afghanistan borders. But now details are beginning to emerge.

This week I visited archaeologist Fredrik Hiebert at the University of

Pennsylvania Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology. There he has some

exquisite pottery shards the Russian government gave him permission to bring

back to the United States from his recent excavations in the Kara Kum desert of

Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan on the Iran and Afghanistan borders.

No American archaeologist had

been there since 1904 when New Hampshire archaeologist and geologist, Raphael

Pumpelly, discovered ancient ruins at Anau in southern Turkmenistan near Iran.

But the Soviets did not develop the Anau site. In the 1970s, Soviet archaeologists

working west of Afghanistan reported vast ruins, all built with the same

distinct pattern of a central building surrounded by a series of walls. Several

hundred were found in Bactria and Margiana on the border that separates

Afghanistan from Russia's Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. But nothing was reported

beyond a few Soviet journals that were never translated.

Then in 1988 after the collapse

of the Soviet Union, Dr. Hiebert first received permission to travel to Anau.

He has discovered it is about 2,000 years older than the Bactria and Margiana

sites further to the east, going back nearly seven thousand years to at least

4,500 B. C., or the Bronze Age. Not only are the oldest shards from there of

high craftsmanship, this past summer Dr. Hiebert also found a black rock carved

with red-colored symbols that, to date, are unidentified but considered to be

evidence of a literacy independent of Mesopotamia. The discovery is

revolutionary to earlier academic thought that Sumeria was the first civilization

with language. Dr. Hiebert will present his findings at an international

meeting on language and archaeology at Harvard on May 12.

Interview -

Fredrik Talmage Hiebert, Ph.D.,

Prof. of Anthropology, Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

and Assistant Curator of Near Eastern Archaeology, Philadelphpia, Pennsylvania:

"Our work joins Mesopotamia and Sumeria in being one of the world's

civilizations in an area we hadn't previously expected to find civilization.

This is far to the north of the cities of ancient Mesopotamia, Iran and even

north of the ancient cities of the Indus civilization. This is in an area that

was formerly part of the Soviet Union, so most western scholars did not have

access to this area.

Then this last year during my

excavations of June and July 2000, we came across a wonderful discovery: an

inscribed stamp seal dated to about 2,300 B. C. that clearly had symbols on it.

These symbols looked to us like writing. We looked around at all the different

systems in the area. Was it ancient Mesopotamian? Was it ancient Iranian or

ancient Indus? We even asked our Chinese scholars if it were ancient Chinese?

And it was none of these.

This small 1.3 by 1.4

centimeters shiny black jet stone carved with an inscription emphasized with a

reddish pigment was found at the Anau site in June 2000 by Dr. Fredrik Hiebert.

Layered in charcoal carbon dated at 2,300 B.C. Photograph courtesy Prof. Fredrik

T. Hiebert, University of Pennsylvania.

So, we are proposing that this

one single stamp seal is the first ever evidence we have of writing among the

cities of central Asia that were found by our Soviet, now Russian, colleagues,

and now where we are working as well. In other words, it's not just a linking

area of the centers of civilization. But it now contains characteristics of

ancient civilizations itself - cities, monumental architecture, a very elite

society such as kings and courts, and now some form of literacy or writing

system. This is very important because what it means is that we can re-write

the history books about the ancient world. We are not really looking at

separate, individually developing civilizations that weren't in contact with each

other or didn't know about each other. It seems quite clear that this new piece

of the puzzle suggests there was a broad mosaic of cultures that knew about

each other and seemed to be growing in relationship with each other. This is

the importance of our work.

HOW DID YOU SPECIFICALLY DATE

THAT SEAL THAT HAS THE SYMBOLS?

The way archaeologists would

date such a single find like that would be to identify what level exactly it

came from in the excavation. And in this case, we were very lucky. It was lying

on the floor of a building and it was actually stratified between different

floors. And on the floor of that particular building, we found some charcoal.

And charcoal allows us to radiocarbon date that level. We had four radiocarbon

dates that allowed us to clearly say it was 2,300 B. C. (4300 years ago) that

the charcoal was deposited (where rock seal found).

ALL OF THIS SEEMS TO BE PUSHING

BACK OUR BENCH MARK FOR THE BEGINNING OF CIVILIZATION BECAUSE YOU HAVE TO HAVE

AN EVOLUTIONARY ARC TO GET UP TO 5,000 TO 7,000 YEARS AGO OF A FULL BLOWN

CIVILIZATION.

Yes, and one of the methods we

use in excavating is what we call stratigraphic excavations where we do very

small sized excavations which are very deep. And these small sized excavations

allow us to compare the development in an open site through time. And at our

site in Central Asia called Anau - just across the Iranian border in the modern

state of Turkmenistan �-we've documented almost continuous growth of the

culture in this area for at least 6,500 years. And that goes all the way back

to the earliest farmers we have in the area. And what's unique and special is

it's clear to see that they used the same forms of farming and herding in

central Asia as did the ancient Mesopotamian people. So, we've got clear

evidence for the interaction and the co-development of farming levels in

central Asia, just as in Mesopotamia.

So, we are looking at a part of

the world, even though it had been forgotten by western scholars, which really

takes its place as a partner in the development from the first farmers about

10,000 years ago up to early villagers when we see the beginning of our

settlement in Anau at Turkmenistan 4,500 B. C., all the way through the

development of these large cities that we are finding out in the deserts. And I

am quite convinced that 5,000 years ago an ancient Sumerian would have some

understanding of what a central Asian was, or what central Asian artifacts were

and vice versa.

HOW BIG IS THE SITE NOW SO FAR

THAT YOU HAVE EXCAVATED?

We've been looking at some of

these large desert oasis sites in part of the Kara Kum Desert of Turkmenistan

which cover an area of 100 miles long by some 50 miles wide. This is an area

that is simply dotted with archaeological sites. We call this an 'ancient oasis.'

It would have been an area watered in the past with irrigation canals and would

have been a lush agricultural oasis where farming would have produced an

abundance of wheat and barley.

Today it's sandy. The sites are

almost gone. It takes excavation to reveal the plans of these buildings. Once

the buildings are excavated, we see they are unlike any other area that we have

previously worked in Mesopotamia or Iran. These buildings tend to be in the 300

to 500 foot length on each side, often having many series of walls that enclose

them surrounded by the fields, the agricultural fields. It's almost like a

building complex with dozens and dozens of rooms inside them. Quite unusual and

apparently quite an organized society.

THAT SOUNDS LIKE IT WOULD

SUPPORT A LARGE POPULATION. DO YOU HAVE ANY SENSE OF THE NUMBER OF PEOPLE AND

WHAT WAS THE WATER SOURCE? WERE THERE ANY WELLS UNDERGROUND OR ANY KIND OF

NEARBY RIVER SOURCE?

It's really hard to predict how

many people would live in a particular building or how long a building was

occupied, whether people living in one part and then another part. It seems

that these large building complexes would support hundreds of people. Probably

not thousands. They are not as big as a traditional ancient city, but their

organization and density of rooms in them suggest it would be a fairly large

population for that area.

About the water source. Clearly,

water was the key to life out in the middle of the desert. And the only way

that people could have lived out there is if they took a local river - and

there were rivers that ran out into the desert - and modify the delta of the

river. In other words, where the river snakes out into the desert, rather than

letting it form a giant jungle morass of thickets, the people must have cut down

the thicket and cleared irrigation canals. Once they did that, they took that

desert oasis and made it bloom. Can you imagine that, 4,000 years ago, making a

desert bloom?

WELL, IT HAPPENED IN EGYPT ALONG

THE NILE?

It certainly did. And in many

ways, these central Asian desert oases are like the Nile in which you could

have one foot in a lush oasis and one foot in the sand right at the edge.

AND IT SOUNDS AS IF THIS WERE

HAPPENING IN MESOPOTAMIA, EGYPT, CENTRAL ASIA, ALL AT THE SAME TIME, ALL BACK

MUCH FURTHER THAN ANYONE EVER REALIZED.

Yes, this is one of the things

that intrigues us all is to imagine a system that we had previously thought may

have existed only 2000 years ago when the Romans were in power in the

Mediterranean and the Han Dynasty was the great Imperial power in China. Now we

are pushing that thousands of years back earlier than that into the Bronze Age.

One of our questions is about how much trade was going on among them? Was there

actually a Bronze Age Silk Road, a 4000 year old Silk Road? I don't think we're

yet able to answer that, but we can talk about the importance of these desert

oases as a pre-Silk Road civilization.

Prof. Fredrik Hiebert holding oldest

ceramic pottery chard dated around 3,500 B.C. from the Anau, Turkmenistan

(Russia) archaeological site. Another Turkmenistan chard near his hand is a

15th century A.D. blue and white copy of a traditional Chinese pattern. Center

is a jagged cylindrical vase around 2,500 B.C. Next to it is another 2,500 B.C.

well-preserved delicate vase. On the silk square is the carved "bone

tube," circa 2,000 B.C.

NOW, ON THE TABLE WITH US, IT

ALMOST LOOK AS IF I AM LOOKING AT DELFT CHINA. HOW DID THIS BLUE AND WHITE,

DELICATE PATTERN COME TO BE IN CENTRAL ASIA ALONG WITH THESE OTHER PIECES? WHAT

ARE WE LOOKING AT? HOW OLD IS IT AND WHERE DID YOU FIND IT?

On the table in front of us are

a series of pottery shards. A pottery shard is a part of a pot that was broken.

These pottery shards are the best thing we have in archaeology because when

they are broken, people throw them away. These are the remains we find most

commonly on the dig. So, I have a selection of ceramic shards which represent

the time scale we have from Central Asia.

The first piece we have is the

blue and white ceramic that has a bird or dragon on it and these curly designs

that do remind us of Delft ceramics. This is a 15th Century A. D. Silk Road

pot. It would have been locally made, but it would have been made in imitation

of Chinese blue and white. And what's interesting about this is that in central

Asia, they are making imitations of Chinese blue and white. And in Europe they

were also making imitations of Chinese blue and white. It was sort of the

Coca-Cola signature of the past.

Moving on chronilogically, we

turn to another well-made pot. It's so thin (knocks on it), you can hear how

finely made it is.

One-eighth

inch thin walls of finely made vase from Turkmenistan, circa 2,500 B. C.

ONLY 1/8TH INCH THICK.

Yes, this is a piece that is

about 2,500 years old, about 2,000 years earlier than the blue and white

ceramic. Incredibly well made. It was obviously done by a master craftsman

potter. this was made up in the desert oasis of Turkmenistan and it reflects a

certain style that the people had. They didn't paint their pottery. You might

think that had to do with the technology of the time, but in fact, it was their

style not to paint their pottery. It's quite nice made. It's sort of buff on

top and on the bottom it's red. They distinctly and purposefully did that. All

of their ceramics from Central Asia is fine from this time period and it

reflects the high level of crafts they had in the area.

Then we move on to three

artifacts, not pottery, but metal and bone artifacts dated to about 2000 B. C.,

so these are about 4100 years old. We are moving back in large jumps of time.

And here we see a bronze ax in the form of a bird's head with a feather going

back and very clear eye.

Bronze

ax in form of bird's head with eye and feather, circa 2,000 B. C.

And what we call a 'bone tube.'

I wish we had a better name for it. They are always polished very finely with

eyes, headdress or hair and some form of necklace or some perhaps a beard. And

these ancient tubes we think were part of the ancient rituals of 2000 B. C. And

the ritual live is another area we as archaeologists can look at. So we can

look at the nature of their houses, the nature of their trade with these stamp

seals we find, the nature of their production such as the pottery and even the

types of religion they had such as the bone tube.

"Bone

tube" carved with stylized head, circa 2,000 B. C.

WHAT DO YOU THINK THE BONE TUBE

WAS USED FOR?

We're not exactly sure, but it

was found in piles of dirt we have analyzed that had a tremendous amount of

ephedra. Ephedra is a type of plant that ancient Zorastrians used to create a

ritual drink that allowed them to hallucinate and get closer to God. It may

well be that the tube was used in some pre- Zorastrial ritual involving

ephedra. Ephedra has medicinal factors. The decongestant Sudafed is made from

the same ephedra chemical. But if you take it in some quantity and mix it with

a poppy or opium, it would have the effect of giving you visions or hallucinations.

IN THE AREA YOU ARE WORKING, IF

YOU WERE GOING TO TIE THEM INTO BLOODLINES OF PEOPLE ALIVE TODAY, WHICH COUNTRY

WOULD BE CLOSEST TO THIS GROUP?

That of course is one of the

questions we would like to know, but don't have the means to answer right now.

I think that if we used the old perspective in suggesting there were individual

civilizations that developed by themselves without much interaction, we might

say Turkish people in the area are the descendants.

DID YOU EVER FIND ANY SKELETONS

DURING THIS WORK?

Burials were very formally made.

They would build a mud brick structure, construct a little house and put

ceramics such as some of these pots here. Sometimes they would leave a ritual

last dinner in with the burials. These have taught us a great deal about the

people. We haven't found as many burials as we have found along the Indus River

or in Mesopotamia, but we've found enough to give us an interesting idea bout

the funereal rituals and the afterlife that the central Asians thought.

IS IT POSSIBLE THERE ARE FEWER

SKELETONS BECAUSE THEY MIGHT HAVE USED A FORM OF CREMATION AND BURNED THEM?

That certainly is possible.

There is a ritual in ancient Persian Zorastrianism that we think would have an

early form in the desert oases that would involve leaving the bodies out to

return to nature.

SO IN A DESERT CLIMATE, THEY

WOULD HAVE BEEN WIND BLASTED AND DISINTEGRATED?

Yes, so the burial record might

not reflect the size of the population, exactly.

AND IT WOULD BE HARD THEN FOR

ARCHAEOLOGISTS TODAY TO KNOW FOR CERTAIN WHAT THAT POPULATION SIZE WAS IN

CENTRAL ASIA?

Yes, there are some things we

can guess at, but we are never going to be able to determine such as the exact

size of the population.

WHAT HAS SURPRISED YOU THE MOST

FROM THE EARLY 1980S TO NOW?

Well, I think the thing that

surprised me most was actually not the archaeological remains themselves, but

the reactions of our colleagues. As we began to peel back the lawyers and

reveal civilization in the desert oases, some people wouldn't believe us. Some

people did believe us. Some people have challenged the origins of this. Some

people have simply ignored this. What we are really seeing is that now from the

1980s to the beginning of the 21st Century is finally an understanding that

this area really takes its place in among the great civilizations of the old

world.

SO, YOU ARE SAYING THAT YOUR OWN

COLLEAGUE SCIENTISTS WERE NOT OPEN MINDED TO THIS DISCOVERY?

I don't know if they weren't

open minded. They hadn't taken into consideration this new area of the world.

And the more we work on it, the more we realize that this is an important part

of the world. It was an important part of the world in the past and it was

directly connected with the other areas. As we work more on this and create a

better understanding of it in English and western languages, the more we are

getting the idea out that we have a large Bronze Age civilization in central

Asia.

COULD THERE HAVE BEEN IN THE

CELTIC WORLD UP IN THE BRITISH ISLES BUILDING THE MEGALITHIC STONE CIRCLES THAT

PRE-DATED ALL OF THIS?

This question of the connection

between the Celtic world and the ancient Near East is one that's been suggested

as much as 100 years ago. The erection of these large stone megalithic

monuments has parallels in the Black Sea world where there are megalithic tombs

made there in the Mediterranean. And perhaps even on the Eurasian steppes.

Nevertheless, to consider those

monumental works part of a civilization wouldn't fall into the same category as

the types of societies we're talking about in central Asia or Mesopotamia

because the builders of the monoliths really didn't have - we don't have

evidence of settled farming or urban life. No cities. None of the domestic

animals and plants. It's a type of complexity that is very different from

central Asia, the Indus Valley and central Asia or China.

So, I think to be open minded,

we have to allow us to understand the deep complexity of building monolithic

monuments, but realizing diversity is also something very important. In central

Asia, people built cities as they did in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley. But

in the areas of Europe, farming took much longer to get there. The farming that

finally entered into Europe after central Asia, thousands of years, and after

the Indus Valley, represent a different type of culture.

WHERE DOES YOUR WORK GO FROM

HERE? WHAT'S NEXT?

We're very excited about

discovering the stamp seal at our site dated to 2,300 B. C. We're certainly

going to go back and look for more evidence of literacy administration of trade

from this time period. We hope to dig deeper to find out how this particular

civilization and site goes in this area. We haven't reached the bottom yet.

We're still digging down. We really look forward to going back for a couple

more seasons at this particular site. Then we hope to expand our research into

looking at the ancient trade routes in the area.

Origins

of the Bronze Age Oasis Civilization in Central Asia By Fredrik T. Hiebert

May 3, 2001

BY FAYE FLAM

KNIGHT RIDDER NEWSPAPERS

PHILADELPHIA -- A major early civilization -- rivaling in sophistication the ones that emerged in the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia, the famed cradle of civilization -- apparently thrived in central Asia between 2200 BC and 1800 BC.

These people, who lived in desert oases in what is now Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, used irrigation to grow wheat and barley, forged distinctive metal axes, carved alabaster and marble into intricate sculptures, and painted pottery with elaborate designs, many with stylized versions of local animals, according to discoveries that have emerged during the past decade or so.

"Who would have thought that now, at the beginning of the third millennium AD, we'd be discovering a new ancient civilization," said Fred Hiebert, an archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia. He has excavated in the region nearly every year since 1988, shortly before the Soviet Union fell.

Some researchers consider writing to be a criterion for any true civilization, and now Hiebert said he thinks he may have evidence for meeting that, too -- a tiny stamp seal carrying four letter-like symbols in an unidentified language. He has dated it to 2300 BC.

On May 12, Hiebert will present his findings at an international meeting on language and archaeology at Harvard University.

"The implication of the seal is incredible," he said, because there's no existing evidence that these people had a written language. And the characters engraved in the stone stamp are unlike any ever seen.

"It's not ancient Iranian, not ancient Mesopotamian. I even took it to my Chinese colleagues," he said. "It was not Chinese."

How could such an advanced culture have been so overlooked?

In the 1970s, Soviet archaeologists working in remote deserts west of Afghanistan came upon vast ruins, each one bigger than a football field. All were built with the same distinct fortress-like pattern -- a central building surrounded by a series of walls.

By the mid-'70s, the Soviet archaeologists had discovered several hundred of these structures in the areas known as Bactria and Margiana.

But their findings remained little known to the outside world because they had never been translated from Soviet journals.

"I was absolutely stunned," said Harvard archaeologist Carl Lambert-Karlovsky, who reads Russian and who, 20 years ago, first read some of the Soviet literature on this unknown world. He transferred his amazement to Hiebert, who was one of his graduate students.

No one knows the extent of this civilization, which may reach beyond Margiana, deep in the Kara Kum desert, and Bactria, which straddles the Uzbek-Afghan border.

Hiebert said he believes that a third area, Anau, outside Ashgabat near the Iranian border, is connected to this civilization, perhaps even the origin of the culture. It is about 2,000 years older, going back to 4500 BC, or the Copper Age.

A New Hampshire archaeologist, Raphael Pumpelly, had discovered ancient ruins at Anau in 1904, but the site did not receive much attention from the Russians. Only now, said Hiebert, are all the pieces, once divided by political boundaries, falling into place.

Planned, not haphazard

Over his years of study in the area where the civilization existed, Hiebert discovered that the various oases "looked like they were in the middle of nowhere, but they are part of the route everyone went on from west to east for thousands of years."

The oases, built in moist areas, created natural stepping stones on a trading route that reached from China through the Indus Valley to Mesopotamia -- all Bronze Age civilizations of the third millennium BC.

The fortress-like buildings of the civilization are larger than the biggest structures of ancient Mesopotamia or China, said Harvard's Lambert-Karlovsky. "The size at the base of some of the buildings is equivalent to the base of the pyramids," he said.

The Soviet archaeologists determined them to be temples because of their size and distinctive layout, but Hiebert, who spent time looking for bone shards, seeds and other remnants of living patterns, came to a different conclusion.

He said the buildings were more like housing complexes, with areas for ordinary people to live, others for the elite, storage areas, and what appear to be areas for ritual.

The dwellers were industrious in other ways as well. In Bactria and Margiana, there was no natural stone or metal. "It was nothing but sand," Hiebert said, and yet the ruins contained elaborate works in alabaster, marble and bronze. "The oasis people would import materials and manufacture them in their own art style."

Lambert-Karlovsky said that many of the artworks, utensils and jewelry were buried with the dead. In an unusual pattern for other early people, the women were buried with more valuables than the men.

Most of the artifacts Hiebert found remain in Turkmenistan -- the politically correct way to do archaeology today. But in his office on the fifth floor of Penn's University Museum, he displays a few.

There is a foot-tall alabaster column, a carved marble plate on a stand, an alabaster bowl, pieces of delicately painted pottery, and a bone pipe, possibly for drug use, carved into a little stylized human figure. Near the pipe, Hiebert found remains of the herb ephedra as well as poppy.

Small bronze axes carry designs, including one of a wild boar, and a piece of pottery is decorated with leopards. "Their world was full of dangers -- wild boars, snakes, scorpions," Hiebert said. These animals show up in their ritual art.

The animal patterns support an idea, suggested by the Soviet archaeologists, that the people practiced an early form of the religion known as Zoroastrianism, which originated in Persia. Animal worship was part of Zoroastrian ritual, as was the use of fire, suggested by some hearths, or altars, found in the remains of ancient buildings.

Hiebert is convinced that this oasis civilization originated around Anau. Not everyone agrees with him. At the forthcoming meeting in Boston, he expects a French team to present findings pointing to a migration from the north, rather than from Anau.

More laboratory work might reveal what the climate was like during the Bronze Age -- probably much wetter and more conducive to farming than it is now.

Hiebert plans to go back in June, armed with satellite maps he obtained with the help of NASA. These reveal wet oasis areas -- where other lost cities are likely to be found.

Central Asia yields ancient civilization

FAYE FLAM,

KNIGHT RIDDER NEWSPAPERS

05/03/2001

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

REGION

A-5

(Copyright 2001)

A major early civilization -- rivaling in sophistication the ones that emerged

in the Indus Valley or Mesopotamia, the famed Cradle of Civilization --

apparently thrived in central Asia between 2200 B.C. and 1800 B.C.

These people, who lived in desert oases in what is now Turkmenistan and

Uzbekistan, used irrigation to grow wheat and barley, forged distinctive metal

axes, carved alabaster and marble into intricate sculptures, and painted

pottery with elaborate designs, many with stylized versions of local animals,

according to discoveries that have emerged over the past decade or so.

"Who would have thought that now, at the beginning of the third millennium

A.D., we'd be discovering a new ancient civilization?" said Fred Hiebert,

an archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia.

Hiebert has excavated in the region nearly every year since 1988, shortly

before the Soviet Union fell.

Some researchers consider writing a criterion for any true civilization, and

now Hiebert thinks he may have evidence for that, too -- a tiny stamp seal

carrying four letter-like symbols in an unidentified language. He has dated it

to 2300 B.C.

On May 12, Hiebert will present his findings at an international meeting on

language and archaeology at Harvard University.

"The implication of the seal is incredible," he said, because there's

no existing evidence that these people had a written language. And the

characters engraved in the stone stamp are unlike any ever seen.

"It's not ancient Iranian, not ancient Mesopotamian. I even took it to my

Chinese colleagues," he said. "It was not Chinese."

How could such an advanced culture have been so overlooked?

In the 1970s, Soviet archaeologists working in remote deserts west of

Afghanistan came upon vast ruins, each one bigger than a football field. All

were built with the same distinct fortress-like pattern -- a central building

surrounded by a series of walls. By the mid-' 70s, the Soviet archaeologists had

discovered several hundred of these structures in the areas known as Bactria

and Margiana.

But their findings remained little known to the outside world because they had

been published in Soviet journals, and never translated.

No one knows the extent of this civilization, which may reach beyond Margiana,

deep in the Kara Kum desert, and Bactria, which straddles the Uzbek-Afghan

border. Hiebert believes that a third area, Anau, near the Iranian border, is

connected to this civilization, perhaps even the origin of the culture. It is

about 2,000 years older, going back to 4500 B.C., or the Copper Age.

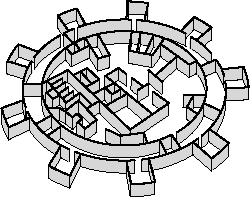

About 4,000 years ago, a

civilization flourished in Bactria, an ancient kingdom in what is now part of

Afghanistan. Archaeological evidence suggests the people who inhabited this

ancient river valley formed a thriving Bronze Age empire, believed to have been

the center of the Zoroastrian religion.

Archaeologists working at the Bactria site found several major architectural

structures believed to have been part of the ancient Bactrian empire. Each

structure was built from dried bricks of a uniform size. One structure was

built in circular form about 40 meters in diameter, similar to the diagram

shown below. Nine compartments were spaced equidistant around the circumference

of the structure and believed to be the bases of towers.

Archaeologists must make reasonable guesses about structures and artifacts

found at archaeological sites. Victor Sarianidi, the Russian archaeologist

excavating the site, believes the building was a temple. Others argue that it

was a palace. Some archaeologists believe the circular building was used as a

fort. When under siege, the Bactrian population could seek refuge behind its

fortified walls. Still other archaeologists believe this building was a

marketplace or bazaar and had no military function.

Now it's your turn to interpret the finds and make your own reasonable guesses.

Imagine you are an archaeologist examining this architectural structure. You

and your team have found artifacts in the walls of the circular building. Study

the list of artifacts. For each artifact listed, determine its function and

what it suggests about the building. Was it used as a fort, a market, a temple,

a palace or something else? After you've identified the artifacts and their

functions, defend your overall conclusion about the role of this ancient

building.

Note: The building floor plan shown above is based on an architectural

complex in another site at Bactria. This is an exercise in critical thinking.

As in archaeology, there are no right or wrong answers. For example, a

spearhead could be found in a marketplace or a fort. The activity is meant to

be open-ended, but you must explain your answers to support your reasoning

(e.g., the spear was found among human or animal remains).